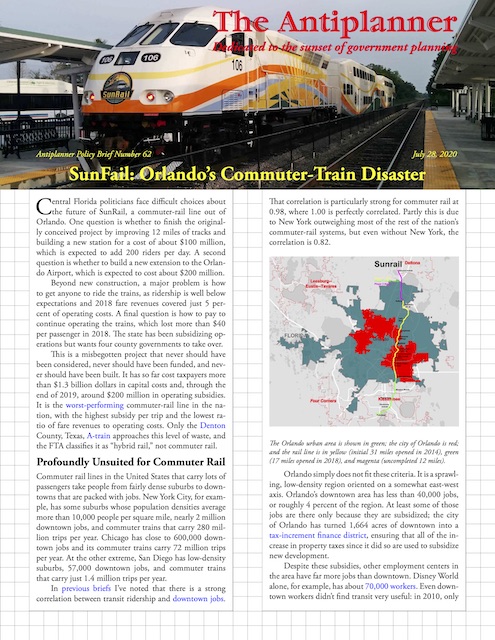

Central Florida politicians face difficult choices about the future of SunRail, a commuter-rail line out of Orlando. One question is whether to finish the originally conceived project by improving 12 miles of tracks and building a new station for a cost of about $100 million, which is expected to add 200 riders per day. A second question is whether to build a new extension to the Orlando Airport, which is expected to cost about $200 million.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Beyond new construction, a major problem is how to get anyone to ride the trains, as ridership is well below expectations and 2018 fare revenues only covered 5 percent of operating costs. A final question is how to pay to continue operating the trains, which lost more than $40 per passenger in 2018. The state has been subsidizing operations but wants four county governments to take over. Continue reading