Transit was hit hard by the pandemic, and one of the hardest-hit agencies was the Virginia Railway Express (VRE). Ridership in April and May 2020 was only 2.5 percent of what it had been the year before. By November 2021, ridership was still only 17.5 percent of pre-pandemic numbers.

Click image to download a three-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a three-page PDF of this policy brief.

VRE operates commuter trains from northern Virginia to Washington DC’s Union Station. It has two lines, one heading west to Manassas and the other heading south to Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania. It is a true commuter-rail operation, with trains heading into Washington in the morning and heading out in the afternoon but not providing on weekends or other times of the day.

VRE’s Fredericksburg line parallels I-95 and its Manassas line parallels I-66.

In 2019, Virginia’s governor, Ralph Northam, proposed a $3.7 billion plan to increase Amtrak and VRE service in the state. In addition to calling for hourly Amtrak trains between Richmond and Washington, the plan proposed a 60 percent increase in VRE service.

Virginia’s next governor, Glenn Youngkin, takes office next week and has already announced his nominee for Secretary of Transportation: a businessman named Sheppard Miller III. Miller is located in Norfolk, which means he is probably familiar with the Norfolk light-rail disaster. That could make him skeptical of Northam’s rail plan, and there are good reasons for that skepticism.

Not an Express

The first thing to note about the Virginia Railway Express is that it is not an express, which in railroad parlance means a train that makes fewer stops so that it can go faster than other trains. Amtrak trains in the Fredericksburg corridor make three to five stops after departing or before arriving at Union Station; 15 out of 16 VRE trains make twelve stops, while the sixteenth makes eight. In the Manassas corridor, Amtrak trains make four stops; most VRE trains make nine.

Though VRE trains are capable of top speeds of 79 miles per hour, frequent stops mean low average speeds. Trains on the Fredericksburg line average 31 miles per hour; trains on the Manassas line average 26. According to Google maps, someone driving the length of each line would save a half an hour on the Fredericksburg route and more than 15 minutes on the Manassas route.

Saturated Demand

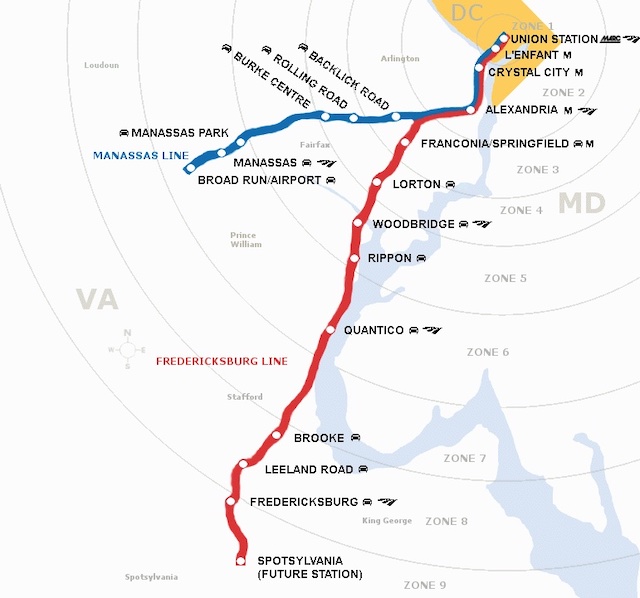

VRE began operating in 1992. Because its fiscal year ends on June 30, Federal Transit Administration data for the operation extend from 1993 to 2020, with some data available for 2021 as well. Based on these data, the chart below shows that ridership responded positively to increases in service between 1999 and 2012. Between those years, a 74 percent increase in vehicle-revenue miles of service led to 162 percent more riders.

Despite continuing increases in service, VRE ridership stagnated after 2012.

After 2012, however, ridership no longer responded to increases in service. Between 2012 and 2019, service grew by 21 percent, yet ridership declined by 6 percent. This suggests that the demand for commuter-rail service has been saturated, and further increases in service would not be worthwhile.

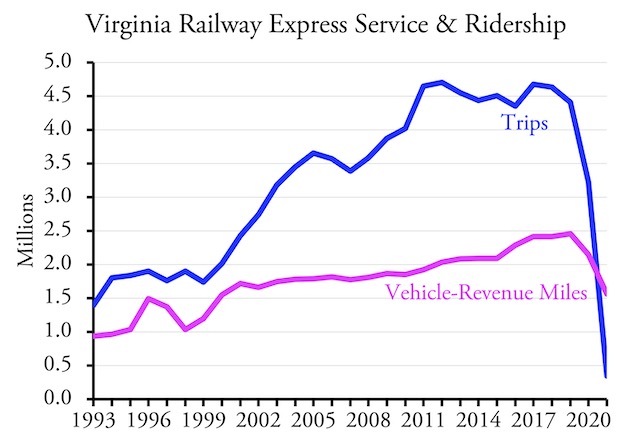

VRE has a target of collecting enough fare revenues to cover half its operating costs, a target that it wasn’t meeting before 2009 but that it met in every year from 2009 to 2019. To reach this target in the last few years, VRE made up for declining ridership by increasing fares from an average of $7.38 in 2012 to $9.53 in 2019.

This target is somewhat deceptive, however, as rail lines have much higher capital costs than buses. While fares may have covered half of operating costs in most years, the capital replacement costs are just as essential for keeping the trains running and are only counted separately because they don’t recur each year. Between 1993 and 2019, capital expenditures averaged $28.4 million per year (in 2020 dollars). When this is added to the cost side, fares only covered about a third of costs.

VRE fares covered more than half of operating costs in most recent years, which by transit industry standards is good but by real world standards is terrible, especially considering annualized capital costs reduce fare recovery to 33 percent.

VRE gets its operating subsidies from county governments, while it relies on the federal and state governments for capital subsidies. The counties that fund VRE—mostly out of gas tax revenues—don’t really care about capital costs since someone else is paying them. Yet they are still real costs.

Pandemic

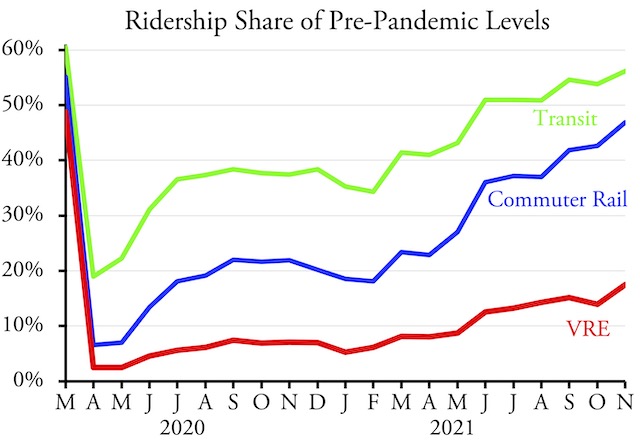

Commuter rail was hurt by the pandemic more than almost any other form of transit, and VRE was hurt more than almost any other commuter-rail system. As of November 2021, the only commuter-rail operation attracting fewer riders, relative to pre-pandemic numbers, than VRE was Minnesota’s North Star.

Despite ridership that remains well under 20 percent of pre-pandemic levels, VRE is still operating 90 percent as many vehicle-miles of service as it was in 2019. This means it is operating as many trains as before, but some of the trains may have one fewer car.

VRE fared much worse during the pandemic and has been much slower to recover than the transit industry as a whole or even commuter-rail systems as a whole.

VRE’s double-decker railcars have between 123 and 144 seats apiece. The average number of riders they carried peaked at 75 in 2011, but as ridership stagnated after that they declined to 55 in 2019. At the beginning of the pandemic, VRE marked three-quarters of the seats “Do Not Sit” for social distancing, but this was probably unnecessary as the average number of riders carried per car fell to less than 7 in 2021.

Given such low ridership, VRE’s continued operations at 90 percent of pre-pandemic service levels made sense only from the perspective that Congress had given them generous funding to do so.

The Future of Downtown DC

Before the pandemic, downtown Washington had well over 400,000 jobs, making it the third-largest concentration of employment in the country after Manhattan and the Chicago Loop. Offices make up 75 percent of downtown DC, and most office workers are able to work at home. Much of the other 25 percent depends on tourism and that was also struck hard by the pandemic.

As of July 2020, 95 percent of downtown Washington office workers were working at home. Hotel revenues were down by 96 percent and retail vacancies had reached record levels. In total, July 2020 economic activity was only 12 percent of 2019.

By mid-2020, 25 percent of office workers had returned to downtown. Hotel revenues were up to 44 percent of pre-pandemic levels. Overall, economic activity in downtown DC was a third of pre-pandemic levels.

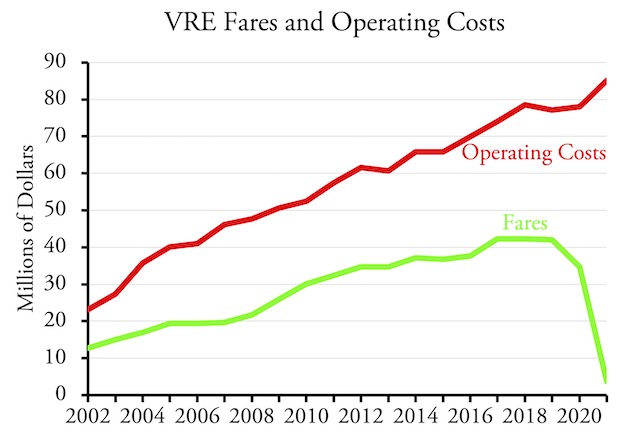

Posting signs discouraging people from sitting in three out of four seats sends a clear message to customers: transit is not safe for your health. Photo by VRE.

While the tourist industry is likely to recover, it appears that a majority of people who once worked in downtown offices believe, and their employers may agree, that they can continue to do the work they need to do at home. As of August 2021, 9.6 million square feet of office space in downtown was vacant, which was a record 17 percent of the downtown area. This suggests that many organizations believed they wouldn’t be moving all their employees back to downtown after the pandemic.

A permanent reduction in downtown economic activity also means less traffic congestion on the roads leading into downtown. That reduces the incentive for people to take transit to work. Considering that the upscale communities served by VRE are most likely to house workers who will stay at home after the pandemic, VRE’s ridership is likely to remain well below pre-pandemic levels even if the pandemic is ever declared to be over.

In the face of these facts, VRE planning and financial documents appear to be quite delusional. The agency’s 2022 budget forecast fare revenues of $18 million, when actual revenues were probably less than half of that amount. With recovery taking place much slower than expected, the agency should consider curtailing service rather than increasing it.

The Bus Alternative

Policy makers enamored with trains often ignore the more modern solution to mass transportation: buses. Buses can go to far more places, serving far more people, without expensive new construction or upgrading of existing tracks to passenger standards.

The VRE route to Spotsylvania parallels Interstate 95 while the route to Broad Run parallels Interstate 66. Both routes have high-occupancy vehicle lanes for part or all of the distance that they parallel the rail lines, which means buses could use them without facing congestion even during rush hours.

Buses could be much faster than trains. Instead of stopping six to nine times between the origins and where the two routes merge in Alexandria, the state or counties could operate non-stop buses from each community served by VRE to Alexandria, where passengers could transfer to the Washington Metrorail system.

At peak ridership in 2012, VRE was able to reduce the taxpayer subsidy to around 40 cents per passenger-mile counting both operating and capital costs. This is pretty good considering that the average for transit nationwide was 58 cents per passenger mile in 2012. By 2019, falling ridership had pushed this close to 50 cents per passenger mile, while the agency’s insistence on operating at 90 percent during the pandemic pushed the subsidy to well over $10 per passenger mile in 2021.

While a subsidy of 50 cents per passenger-mile was competitive with many commuter-bus operations, which cost an average of 42 cents per passenger-mile in 2019, many commuter buses are significantly less expensive. The Woodlands, a suburb of Houston, runs commuter buses to downtown Houston at a cost of just 7 cents per passenger-mile in 2019. The Yuba-Sutter Transit Authority runs commuter buses from Yuba City and Marysville to downtown Sacramento at a cost of 11 cents per passenger-mile. San Diego’s commuter buses cost just 19 cents per passenger-mile. Several others cost less than 20 cents a passenger-mile; the key is tailoring the size and frequency of buses to fill a high percentage of seats.

Motorcoaches with comfortable seats, wifi, powerports, and other amenities attract large numbers of commuters in the New York, Los Angeles, Houston, Atlanta, San Francisco, and other urban areas. Rather than expand VRE service, as proposed by Governor Northam’s plan, the counties supporting VRE should consider transitioning from trains to buses.

Conclusions

Given the exceedingly low expectations of the U.S. transit industry, VRE was a success story as of 2012. Ridership had grown much faster than expenses, which meant that overall costs and subsidies per passenger mile had steadily declined. That success was dampened, however, by the stagnation in ridership after 2012, and it was absolutely killed by the pandemic.

With ridership declining after 2012 despite increased service, Governor Northam’s proposal to increase service another 60 percent was unlikely to produce any positive results. While that may have been debatable in 2019, what is not debatable today is that the long-term effects of the pandemic will be a dramatic decline in demand for transit service to downtown DC. Any expansions in VRE service should be put on hold and counties should seriously consider replacing trains with buses.

Buses could be much faster than trains. Instead of stopping six to nine times between the origins and where the two routes merge in Alexandria………..”

Vans can be faster than buses… “Demand based transit” constitutes, finding a group wanting to go somewhere, informing upon destination.

”

Posting signs discouraging people from sitting in three out of four seats sends a clear message to customers: transit is not safe for your health.

” ~anti-planner

I suspect they would claim it’s about distancing and safety. They are both correct.

One of the ideas w/ hybrid is that we’ll see more donuting in metros. More of the downtown workers that pop into the office once or thrice a week, living even further out.

If that’s the case, if people feel they can get things done – if if that is taking a nap – while on VRE, the number of stops isn’t a deal breaker. It could even be played as feature. Then again, these are the people that after 2 years don’t realize that:

a) everyone w/ 5 brain cells understands social distancing

b) blanking out all those seats not only conveys things ain’t safe but also no many use this thing