When the pandemic hit, I thought it would slow down sales of existing homes. Instead, home sales in 2020 reached their highest level since the peak of the housing bubble in 2006. I also thought that the pandemic would slow new home construction. Instead, by the end of the year, new home starts also reached their highest level since 2006. When people began moving out of Manhattan, San Francisco, and other big cities, I assumed most of them would consider the moves temporary and would be renting at their new locations. Instead, homeownership took its biggest year-over-year leap since at least 1960 and probably in U.S. history, reaching levels not seen since, you guessed it, the 2006 bubble.

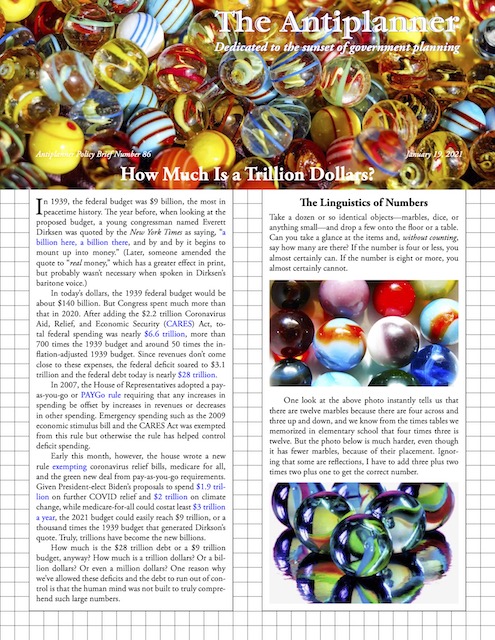

Click image to download a three-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a three-page PDF of this policy brief.

Information about moving trends isn’t always clear. In September, Bloomberg writer Marie Patino questioned the conventional wisdom that people were moving out of big cities or indeed that more people were moving than in previous years. However, her data were based on how many people were hiring companies like United Van Lines, when in fact most moves don’t use professional movers. We won’t really know the truth until the dust settles a year or two from now, but we can get a glimmer of that truth by digging into what data are available. Continue reading