Transit in 2022 carried less than 1 percent of passenger travel in 461 out of the nation’s 487 urban areas and less than half a percent of passenger travel in 426 of those urban areas. It carried more than 2 percent in only 7 urban areas and more than 3 percent in just two: New York and San Francisco-Oakland. These numbers are calculated from the 2022 National Transit Database released last October and the 2022 Highway Statistics released last month, specifically table HM-72, which has driving data by urban area.

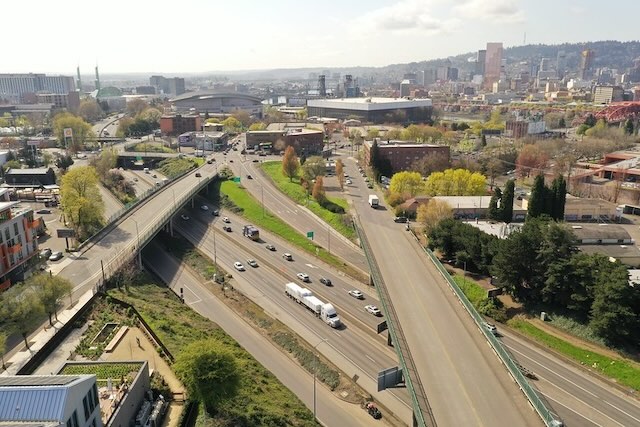

Highways were a little less congested in 2022 than before the pandemic. Oregon Department of Transportation photo.

In 2019, transit carried 11.6 percent of motorized passenger travel in the New York urban area, a share that fell to 8.5 percent in 2022. Transit carried 6.8 percent in the San Francisco-Oakland area in 2019, which fell to 3.6 percent in 2022. Transit carried around 3.5 percent in Chicago, Honolulu, Seattle, and Washington urban areas, which fell to 2.5 percent in Honolulu, 2.1 percent in Seattle, and less than 1.8 percent in Chicago and Washington in 2022. Anchorage, Ithaca, and State College PA are the only other urban areas where transit carried more than 2 percent of travel in 2022.

If you do the calculations, you’ll find that transit carried a phenomenal 14.2 percent of passenger-miles in Hanford, California. However, this is because Hanford is the headquarters for the state’s vanpool program so all vanpool passenger-miles in the state are attributed to Hanford.

The 2022 National Transit Database is based on transit agency fiscal years while the 2022 Highway Statistics is based on the calendar year. To compare calendar year transit passenger-miles with autos, I multiplied passenger trips in calendar year 2022 by the average miles per trip in each urban area from the 2022 National Transit Database. Highway Statistics table HM-72 reports daily vehicle-miles traveled; I multiplied this by 365 to get annual and by average vehicle occupancies of 1.52 to get passenger-miles.

The sad thing is that numerous transit agencies are seeking federal dollars to expand their systems at a time when their actual ridership is miniscule. Transit’s share of motorized travel in Baltimore has gone from 2.0 percent in 2019 to 1.0 percent in 2022. Yet Maryland’s governor wants to spend billions on a new Baltimore light-rail line despite the fact that the state recently announced that its seven-years-delayed Purple line, which already had a 200 percent construction cost overrun, is suffering even more delays and cost overruns.

Even more pathetic, St. Louis transit’s share has fallen from 0.6 percent to less than 0.4 percent of travel, yet Metrolink is eager to build new light-rail lines that will cost more than a billion dollars. It is worth noting that, in both Baltimore and St. Louis, bus systems carried more riders before the rail lines opened than bus plus rail carried in 2019.

Recent research based on the 2022 National Household Travel Survey concluded that a large share of the decline in transit ridership between 2019 and 2022 is permanent. Except where transit agencies convince state and local politicians to simply give away all transit rides, I don’t think ridership is going to increase much above the 73-75 percent of prepandemic levels experienced over the last five months of 2023. Thus, spending huge gobs of money on rail transit will be a complete waste.

Other highway data, specifically table VM-1, shows that miles of driving increased by 2 percent in 2022, but passenger-miles of highway travel declined by nearly 6 percent. That’s because vehicle occupancies from before 2022 were based on the 2017 National Household Travel Survey while 2022 occupancies were based on the 2022 survey. The 2017 survey found an average of 1.67 people per vehicle, which was consistent with previous surveys (which are done about every five years). But the 2022 survey showed occupancies dropping to 1.52.

I noted this decline last fall and since then the authors of the survey haven’t said anything about why they think this decline took place. It might seem reasonable to think that the pandemic would reduce carpooling, except that American Community Survey data found that carpooling fell only slightly from 8.9 percent of commuting in 2017 to 8.6 percent in 2022. Moreover, the travel survey found that the greatest declines in vehicle occupancies were for shopping and other household trips.

It seems likely that the decline in vehicle occupancies is due to a shrinkage of average household sizes. In 2017, the average household had 2.71 residents; in 2022 this had fallen to 2.55. Going over historic data, vehicle occupancies have roughly equalled household sizes minus 1. The change in occupancies from 2017 to 2022 appears to follow this trend. Most of the drop in household sizes happened by 2021, when household sizes averaged 2.60. It might be reasonable to lower the 2021 highway passenger-miles by a small amount to account for this, but the Department of Transportation won’t do that.

In any case, even with the decline in vehicle occupancies, highways still accounted for 87 percent of total passenger-miles in 2022, about the same as in 2019. I calculated this by filling the 2022 highway data from table VM-1 into the Bureau of Transportation Statistics passenger-miles table. However, highways maintained this percentage because the Federal Highway Administration estimated that non-transit bus passengers-miles increased by more than 8 percent since 2019. Since I already considered the bus number to be about three times too high, and there has been less than a

Vehicle-mile numbers are based on hundreds of traffic counters scattered around the country. The sorting of those numbers into categories such as autos, motorcycles, semi-trucks, and buses is based on Federal Highway Administration estimates. If the bus numbers are corrected by reducing them, then vehicle-miles of other categories of vehicles have to be increased. Maybe all of that increase is large trucks that the FHwA confused with buses, but at least some of it might be automobiles. Table VM-1 indicates that auto passenger-miles declined from 76.5 percent in 2021 to 74.2 percent in 2022, mainly due to reduced vehicle occupancies. While that’s not unreasonable, I suspect a correction in bus data would increase auto’s share of travel in both years.

Since transit passenger-miles are fairly reliably estimated in the transit database, it is unlikely that correcting non-bus passenger-miles would change transit. Transit’s share of the nation’s passenger-miles fell from 0.85 percent in 2019 to 0.52 percent in 2022. Amtrak’s share, meanwhile, fell from 0.10 percent to 0.08 percent while airlines’ share grew from 11.8 percent to 12.2 percent.

Highway Statistic also keeps track of highway finance, including how much of highway costs are paid for out of tolls, how much out of gas taxes and registration fees, and how much out of general funds. The Federal Highway Administration has not yet posted all of the relevant tables for this, so I’ll take a closer look in a future post.

Where do we get the room to expand more highways in existing areas?

One method to improve existing car travel is to convert to roundabouts.

Roundabouts are overrated. They don’t perform better than signalized 4-way intersection with **protected-dedicated left/right turn lanes,** which was, for a time, almost exclusively a US tool. Results from studies that measure the effects of roundabout conversion fall pray to selection bias: the intersection that was converted did not have auxiliary turn lanes.

The EU did not adopt auxiliary turn lanes ubiquitously on arterial roads, like the US did, until the 1990s-2000s.

“ The sad thing is that numerous transit agencies are seeking federal dollars to expand their systems at a time when their actual ridership is miniscule.”

What’s worse is that highways are being starved of money that could have a serious impact on reducing congestion, thereby improving the economy, improving mobility, reducing the cost of driving, and even reducing carbon and its global warming effects.

Misdirected government spending is making matters worse, not better.

But we’re meant to believe “This country has dismantled public transit over the last 70 years for the betterment of cars”

Even if that were true; transit would not have stopped the rise of the automobile.

Since 1975 Fuel economy of cars grew 250%

Rail transit systems are ingrained with a operating type that makes them severely vulnerable to loss fares. Rail transit is inferior to buses because of its inflexibility.

Transit was king when cities were on top. Transits relevance to urban economics is less important because urban areas are becoming less relevant to economy.

– The US has a super efficient freight rail system that can move trillions tons goods/commodities at extremely low labor cost. This puts us economic advantage in warehousing and goods distribution over EU and Asia. Bar codes and the international shipping container means we don’t have to open them to move its specific contents.

Meanwhile Europe is now having to build multi-story warehouses https://www.us.jll.com/images/amer/us/research/jll-multistory-warehouses-and-their-towering-future-social-1200X628.jpg

– US has 15,000 Airports or runways, air distribution of packages and freight is ubiquitous on global level.

– Urban land prices, have made industries like steel making, car production and machine part fabrication insoluable, at this point, electric power has replaced coal/coke so American industry doesn’t really pollute much anymore, and is also quieter, so factories/industry in suburbs are not only tolerable, but transportation makes them convenient.

– historic seaports have too shallow a draft to accommodate the supermassive container vessels

– Energy in USA is cheaper than Europe and Japan, which benefits Energy intensive industries like metal processing, concrete making. BMW’ largest factory…..is in South Carolina.

– Lastly, thing most people forget, USA has more entrepreneurs and self employed people than EU and Japan. They require on demand transportation, that only cars fulfill.

Cyrus992,

Existing urban areas should be allowed to expand horizontally with construction of new freeways to serve those expansions. We shouldn’t need to build many new freeways in most areas that have already been developed, but where we do, we can use the Selmon Extension model of building elevated lanes supported by piers in the median strip of the existing freeway.

It depends on how the expansions are done horizontally though. If they are sunken or in a parkway fashion, then the undesirable impacts would be less. In others words, pinavia interchanges beat stacked ones.

Which leads me to the model you presented. The issue is that the visual impacts are concerning. Also they are one lane in either direction which means that the tolls would be very high to address the high demand in some areas.