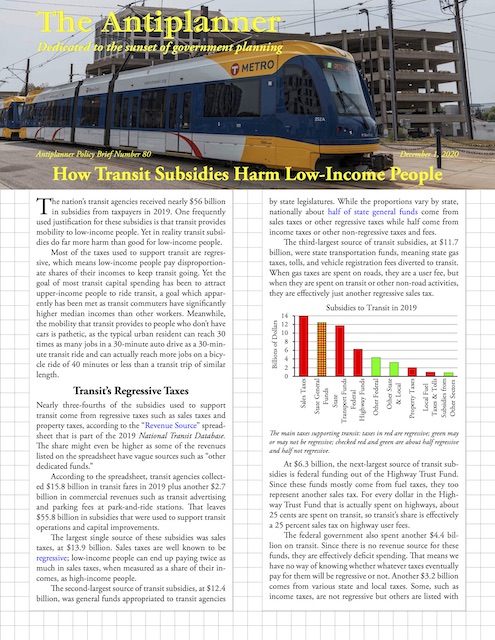

The nation’s transit agencies received nearly $56 billion in subsidies from taxpayers in 2019. One frequently used justification for these subsidies is that transit provides mobility to low-income people. Yet in reality transit subsidies do far more harm than good for low-income people.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Most of the taxes used to support transit are regressive, which means low-income people pay disproportionate shares of their incomes to keep transit going. Yet the goal of most transit capital spending has been to attract upper-income people to ride transit, a goal which apparently has been met as transit commuters have significantly higher median incomes than other workers. Meanwhile, the mobility that transit provides to people who don’t have cars is pathetic, as the typical urban resident can reach 30 times as many jobs in a 30-minute auto drive as a 30-minute transit ride and can actually reach more jobs on a bicycle ride of 40 minutes or less than a transit trip of similar length. Continue reading