In the Antiplanner’s not-so-humble opinion, Fortune magazine made a mistake in declaring Henry Ford to be the businessman of the twentieth century. True, Henry Ford made a lot of cars. But Henry Kaiser built roads, dams, houses, hotels, ships, and planes. He made cement, steel, magnesium, aluminum, and a variety of other chemicals and building materials. He funded and built the first and still the greatest health maintenance organization in the world.

Plus, he also made cars. Chances are, you see a car made by one of his former companies just about every time you go out on the street.

To show that Kaiser was the epitome of an entrepreneur, I’ll present Kaiser’s story in four segments: through 1939, the war years, the post-war years, and Kaiser’s Hawaii ventures, with a wrap-up segment about his legacy.

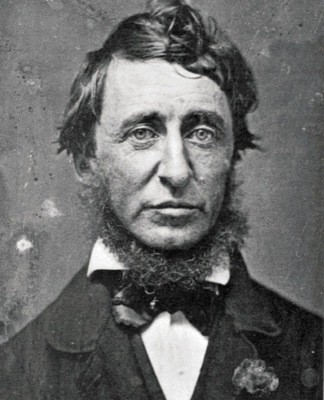

Probably the most famous photo of Hill, circa 1902. Could that be a Thoreau pencil in his hand?

Probably the most famous photo of Hill, circa 1902. Could that be a Thoreau pencil in his hand?